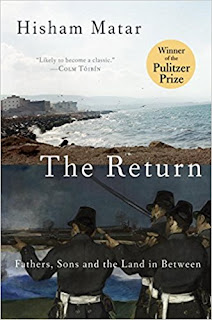

In his memoir

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between, Hisham Matar tells readers the intertwined stories of his father Jaballa Matar, a leading dissident in Libya under Muammar el-Qaddafi, and his fierce love of country and culture; his father's kidnapping and imprisonment in 1990 for his political activities; and his own return to Libya in 2012 after the fall of the Qaddafi regime to try to discover his father's fate. Jaballa was kidnapped when Hisham was only nineteen years old, and Hisham would never see his father again. The narrative takes readers simultaneously both back in time to Libya's past and Hisham's childhood memories of his father, and forward in time as he makes the journey to Libya, reunites with family, and pursues the answers to his questions about his father's fate.

His memoir attempts to answer the question, "What do you do when you cannot leave and cannot return?" It is both a narrative history of Libya and a personal statement of loss, love, grief, and the possibility of consolation. In an interview for the

New York Times, John Williams asked Matar, "You spoke to former prisoners, including your own uncle, as part of your research. What was the most surprising thing you learned from them?" He replied, "I learnt something about the power of stories, and how through them we can travel through time and share, at least in our imaginations, former aspects of ourselves. Most of all, I learnt that we can endure great suffering and survive, mostly intact yet altered."

What do you think? Why did Hisham Matar write The Return as a memoir even though he had already written two semiautobiographical novels, In The Country of Men, from the point of view of a nine-year-old boy, and Anatomy of a Disappearance, from the point of view of a teenaged boy, about these same events? Describe his organizational structure in The Return, his use of time and place. What is the effect on you as a reader? And what about his tone, his attitude toward his subject and toward us as his readers? Matar alludes to many other writers who address the experience of exile and to classic literary examples of father and son relationships. What do these references add to Matar's story? In a review of The Return for The Washington Post, Tara Bahrampour notes, "In a book that does not shy away from painful details, the event it hinges on--his father's arrest--is strikingly absent." Why do you think that Matar made this narrative decision? Why did he delay his return to Libya after the fall of the Qaddafi regime, even contemplating the "immaculate idea" of never returning? Why does he ultimately decide to go? In an article for the New Yorker June 6 and 13, 2016 Issue about childhood reading titled The Book, Matar tells of the book that most

influenced him, one that he has never read and of which he does not even know the author or the title:

I don’t remember what the passages read aloud were about, exactly. What I do remember is that they relayed the intimate thoughts of a man, one suffering from an unkind or shameful emotion, such as fear or jealousy or cowardice, feelings that are complicated to admit to, particularly for a man. But the honesty of the writing, its ability to capture such fluid and vague adjustments, was in itself brave and generous, the opposite of the emotion being described. I also remember being filled with wonder at the way words could be so precise and patient, illustrating, as they progressed, what even the boy I was then somehow knew: that there exists at once a tragic and marvellous distance between consciousness and reality. Given the books that had been read to me, this couldn’t have been the first time that I encountered such writing, but, for some reason, on this occasion I registered its full impact on me. What struck me, too, was the new silence that the passages left in their wake. They created, at least temporarily, among these political men, who seemed to me to function under the solid weight of certainty, a resonant moment of doubt.

Do you see any

correspondences between Matar’s description of this influential book and its

effect on him and his own writing choices in The Return? Can his title,

The Return, be read in several different ways? What did you learn about the Arab world, its history, culture, and current political situation, from reading

The Return?

We hope you will join the discussion: Tuesday, July 11, at 6:30 p.m. at Main Library; Thursday, July 20, at 11:00 a.m. at West Ashley Branch Library; and here on the blog.